Americans in Paris and the Avant-Garde Cabaret

After World War I, Paris became the cultural capital of Europe, and Americans flocked to the city. Here, creative experimentation was boundless, as Parisians were generally more open-minded and tolerant about politics, sexuality, nightlife, and art. While America was deep in the throes of racism, France fell in love with jazz and black performers—notably, Josephine Baker, who created a sensation. Parisians also embraced non-binary performers, like Barbette, who quickly befriended Baker, Jean Cocteau, and Man Ray.

We all came to Paris—it was where we had to be. —Gertrude Stein

These icons of progression, acceptance, and creative fervor live on in the images created by the photographers, posterists, and writers who admired them. Here, we’ll take a deeper look at the legacies of Josephine Baker and Barbette through the posters created for them.

All posters will be available in our 79th Rare Posters Auction on October 27, 2019.

Josephine Baker (1906-1975)

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Baker was immediately exposed to music by her parents and performed with a vaudeville troupe as a teenager. At 15, she traveled to New York City and landed a role in a Broadway chorus line, for which she was praised. By 19, she was bound for Paris where she opened La Revue Nègre in 1925; at this point, she was one of the only black Americans there. And she became an instant star: her nearly-nude erotic dancing captivated audiences, and she soon became a headline act at the Folies-Bergère. It wasn’t just Parisians who loved her—Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and Paul Colin were all fascinated by her and created work inspired by her.

But she did not receive the same support in America, and this, in combination with the country’s racial segregation, persuaded her to give up her American citizenship in exchange for a French passport. Despite this, Baker was arduous about political engagement, and not only served the French military intelligence during World War Two, but also participated in the American civil rights movement alongside Martin Luther King, Jr.

Baker was a revolutionary: she transcended stereotypes, merged and conflated cultural norms, shaped fashion and cabaret performance practices, and fought tirelessly for equality.

37 1/8 x 55 3/4 in./94.2 x 141.8 cm

Est: $6,000-$8,000

Josephine Baker may have exchanged the feathers and diamonds for overalls and penny loafers, but her charm and undeniable stage presence are ever-present in this shimmering gold design. “Die Königin der Revue,” or “Parisian Pleasures,” was a French-German silent film that stars Baker as a down-on-her-luck but aspirational young performer. Though she misses the deadline for a Cinderella-esque call for the smallest feet in Paris, she surreptitiously arrives at the event to prove that only her feet fit the shoes. And of course, her career as a star performer is sealed.

22 7/8 x 34 3/4 in./58 x 88.4 cm

Est: $1,600-$2,500

In 1928, Josephine Baker went on a whirlwind tour throughout Europe and spent one month performing in Budapest at the Royal Orpheum Theatre. Wherever she went, there were “more mobs… It was the same in Budapest; she leaped onto an ox cart to get away from the citizens who welcomed her. ‘They tore my dress apart, they wanted to see me naked'” (Josephine, p. 157). Tibor Réz Diamant’s graphic promotion for that show is now an iconic image. Perhaps Ehrenfeld took note when designing this announcement for Baker’s shows at the Red Mill in Budapest. The floating head, the sapphire blue eyes, and the ebullient smile are all shared characteristics between the two designs—but Ehrenfeld’s is perhaps humbler, and definitely much rarer.

29 3/4 x 45 3/8 in./75.5 x 115.3 cm

Est: $1,400-$1,700

Josephine Baker’s infectious spirit is immortalized in this 1935 French film in the style of Pygmalion—and Baker is the beggar-turned-socialite starlet. She plays Alwina, a young Tunisian woman who catches the attention of Max, a novelist visiting her homeland for creative inspiration. She becomes both the subject of his newest novel and the object of his tutelage, as Max transforms her into a proper socialite lady to accompany him to Paris. He introduces her as Princesse Tam-Tam, and naturally, she’s a hit—especially when she disrupts a Paris ball with a quintessential Josephine Baker cabaret dance. Péron’s promotion is vibrant but refined, allowing Baker to be the rhythmic highlight.

30 3/4 x 46 3/8 in./78.2 x 117.8 cm

Est: $1,400-$1,700

With just a hint of Josephine Baker’s banana dance, this graphic image promotes the film “Zouzou,” whose greatest acclaim is featuring Baker as the first black woman to star in a major motion picture. As a child, Baker’s Zouzou is a traveling circus performer who has been paired with a non-blood-related twin, Jean. Even when they’re older, Jean treats her as a sister, but Zouzou falls in love with him. Through this lovelorn drama, Zouzou eventually becomes a star performer in her own right. The film was released in 1934, so we presume the poster was re-printed to accompany Baker’s 1945 film release, “The French Way.” Rare!

30 1/4 x 36 3/4 in./77 x 118.6 cm

Est: $1,700-$2,000

Girbal’s elegant design adapts a photograph by Harcourt to promote Josephine Baker’s post-war record, “Encores Américaines.” During the war, Baker was a spy for the French Resistance and was a dedicated activist in the Free France effort; she not only collected key information for the French military intelligence, but also performed across Europe and in Morocco. The Columbia catalogue included her songs “Brazil” and “Besame Mucho,” as well as a caption that read, “Thank you, charming officer, for having been heroic and for singing once again for us.”

Barbette (1898-1973)

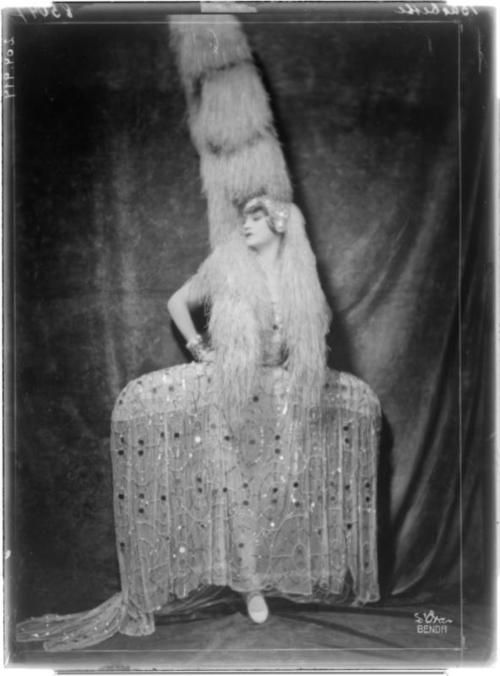

Barbette—the pseudonym of Vander Clyde—was born in Round Rock, Texas in 1898. As a child, he fell in love with the wire act at the circus and resolved to become a performer. And he was emphatically resolved: he worked in the cotton fields to pay for visits to the circus, practiced walking along his mother’s steel clothes line for hours, and graduated from high school at just 14 years old. He then launched his career with the Alfaretta Sisters after one of the sisters unexpectedly died. The surviving sister thought that it was more dramatic for women to perform the acrobatic stunts, and so Barbette agreed to dress as a girl.

By 1919, he had developed a solo vaudeville act as Barbette, which debuted at the Harlem Opera House in New York City. He performed trapeze and wire stunts in full drag, maintaining the aura of femininity until the very end—when he stunned audiences by removing his wig and striking masculine poses. They loved it. His success led him to Europe in 1923, and he performed at the Moulin Rouge, the Alhambra Theater, and the Folies-Bergère. There, he became friends with Josephine Baker and Jean Cocteau, the latter of whom wrote considerable praise for his performances. Cocteau also introduced him to Man Ray, who later captured Barbette’s gender transformation in stunning photographs.

The young American who does this wire and trapeze act is a great actor, an angel, and he has become the friend to all of us. Go and see him … and tell everybody that he is no mere acrobat in women’s clothes, nor just a graceful daredevil, but one of the most beautiful things in the theatre. Stravinsky, Auric, poets, painters, and I myself have seen no comparable display of artistry on the stage since Nijinsky.

—Jean Cocteau

Barbette continued to perform until the mid- to late-1930s. Tragically, he suffered a terrible fall, breaking both legs and contracting polio. He was in extreme pain and had to undergo extensive rehabilitation to be able to walk again; performing was out of the question. But Barbette continued to work creatively as artistic director and aerialist trainer for a number of circuses, including the Ringling Bros. He also served as a consultant to several films, most notably offering his coaching on gender illusion for “Some Like it Hot.”

Though Barbette took his own life in 1973, his legacy lives on in books, photographs, films, musicals, and posters. He made the world fall in love with his wild and unapologetic gender fluidity and creative experimentation, and became an important role model for many more.

15 1/2 x 23 1/2 in./39.5 x 59.8 cm

Est: $2,500-$3,000

Gesmar might be best-known for his costume designs and lithographs for the “Queen of the Paris Music Hall,” Mistinguette—but his talents benefitted many performers, including Barbette. Here, he presents Barbette’s lithe figure enshrouded in the plumes of feathers that he loved to don, which was surely a visual marvel for audiences. This rare poster was created for his stint at the Casino de Paris; this is the smaller size.

Barbette by Man Ray

For more on Barbette:

- Read Francis Steegmuller’s 1969 New Yorker article, “An Angel, A Flower, A Bird”

- Read Albert Goldbarth’s novel/poem inspired by Barbette, “Different Fleshes” (most, but not all, of the book is available from Google Books)

- Read Jean Cocteau’s Le Numéro Barbette, which includes Man Ray’s portraits

- Watch Jean Cocteau’s film, “The Blood of a Poet,” which includes an appearance by Barbette

- Watch Alfred Hitchcock’s “Murder!”, which was inspired by Barbette

- Watch the Barbette-influenced “Victor/Victoria” from 1933

- Watch “First a Girl,” the 1935 remake of “Victor/Victoria”

- Watch the 1983 adaptation of “Victor/Victoria;” it can be rented from Amazon and iTunes